Introduction

The late 19th century saw American middle-class eating culture develop from eating mostly at home to frequently dining out at restaurants. Culinary exploration became a pastime. Mid-19th century Chinese restaurants started in kitchen basements, serving recent Chinese immigrant populations. By the 1890s, many Americans wanted to eat food from abroad, and their patronage presented opportunities for Chinese restaurants to expand. Despite the passing of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entering the United States, Chinese dining culture was not under attack, as were the Chinese workers.

Chinese restaurants in the 1890s reflect a period of intense transnational exchanges in history, when restaurant owners balanced Exclusion Act discrimination with catering to White Middle-Class American tastes. At the same time, Chinese chefs still represented their cultural background. Historian Yong Chen explores Chinese American dining from 1849 through the early 2000s in his article “The Rise of Chinese Food in the United States” in The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Chen identifies the 1890s as the second stage of Chinese American dining, when “white middle-class tourists and food connoisseurs ‘discovered’ Chinese food as a culinary novelty.”

The images below explore the “novelty” of Chinese dining through newspapers, menus, magazines, and more at the turn of the 20th century. Among these sources, Chinese food crosses social and political lines to highlight foundational figures in Chinese American history.

IN THE NEWS

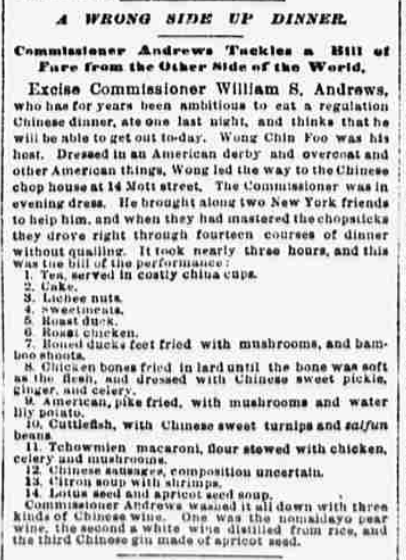

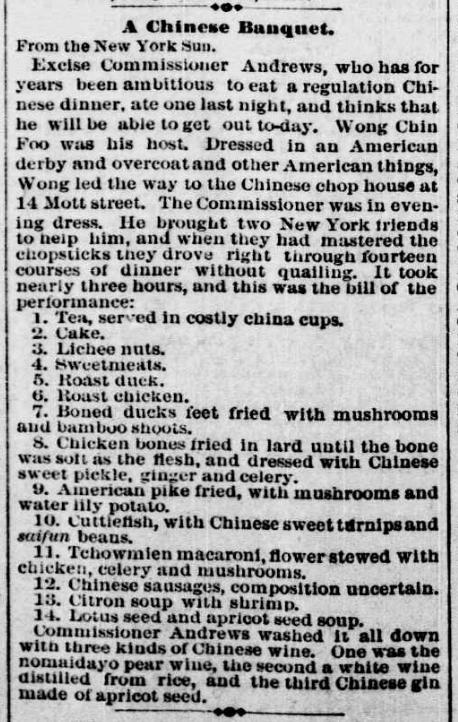

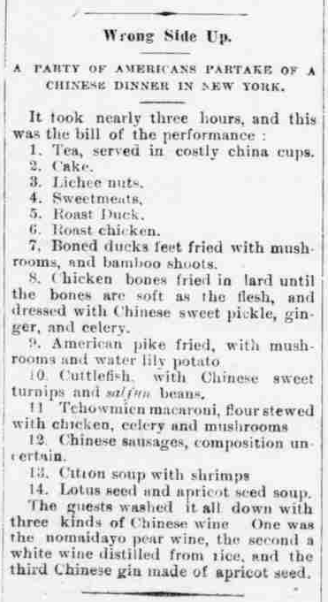

On Tuesday, November 23rd, 1886, the New York Sun reported on a special dinner in Chinatown. Tax commissioner William S. Andrews was invited to dinner by Chinese community member Wong Chin Foo. Though reporters from the Sun reserved the front page new space for eye-catching headlines, “Mrs. Robinson in Peril” and “Cashier Merrill’s Divorce,” the front page also highlighted Andrews’s trip to a Chinese restaurant on Mott Street. Reporting under the title “A Wrong Side Up Dinner,” the Sun’s article shows the novelty interest in Chinese dining.

“Dressed in an American derby and overcoat and other American things, Wong led the way to the Chinese Chop house on 14 Mott Street”

Soon, “A Wrong Side Up Dinner” made its way into newspapers across the country. The Evening Star (Washington DC) and the Daily Globe (St. Paul, MN) headlined “A Chinese Banquet,” while the News and Citizen (Morrison, VT) copied the Sun with “Wrong Side Up.” Years after the story first ran, the banquet gathering made its way into the 1889 culinary guide, Stewards Handbook and Guide to Party Catering. In this book, editor Jessup Whitehead categorized the event into Section 4 – A dictionary of dishes, culinary terms, and specialties. See below how the articles and texts differed in title, tone, and content.

Look closer into the articles paired with “A Wrong Side Up Dinner.”

Orange and Yellow articles focus on negative events like deaths or robberies.

Blue articles share positive or neutral news.

The red box highlights the Chinese restaurant article.

the Americans “mastered the chopsticks” and “ate without quailing.”

What did American diners already know about Chinese dining? Wong Chin Foo, who organized the widely reported dinner with Andrews, was known for his speaking and writing in support of the Chinese American community. Historian Scott D. Seligman describes Wong Chin Foo’s work in his book, The First Chinese American. In addition to hosting private dinners, Foo published general articles which he sold to major periodicals like the Cosmopolitan magazine.

Authoring “The Chinese New York” for the 1888 edition of Cosmopolitan, Foo simplified the world of Chinese cuisine in America. He advocated against rumors of Chinese people eating rats and even offered $500 to anyone who could bring proof of the rat stereotype.

Foo made Chinese food more accessible to English speakers, printing romanized Chinese and in-depth dish descriptions in his magazine articles. He wrote to correct biases against the Chinese community, including an entire section on restaurant cleanliness, at a time when public hygiene was criticized by reformers and the government, who had embraced Progressive sentiments. Foo used food to sell a positive depiction of Chinese life and culture to American readers.

Though Foo profited from his writing, making money by selling excerpts and articles to many periodicals in the late 19th century, his work portrayed the Chinese American community positively when anti-Chinese sentiment was at an all-time high.

Attention to Detail

Chinese Restaurant Kitchens

On the menu

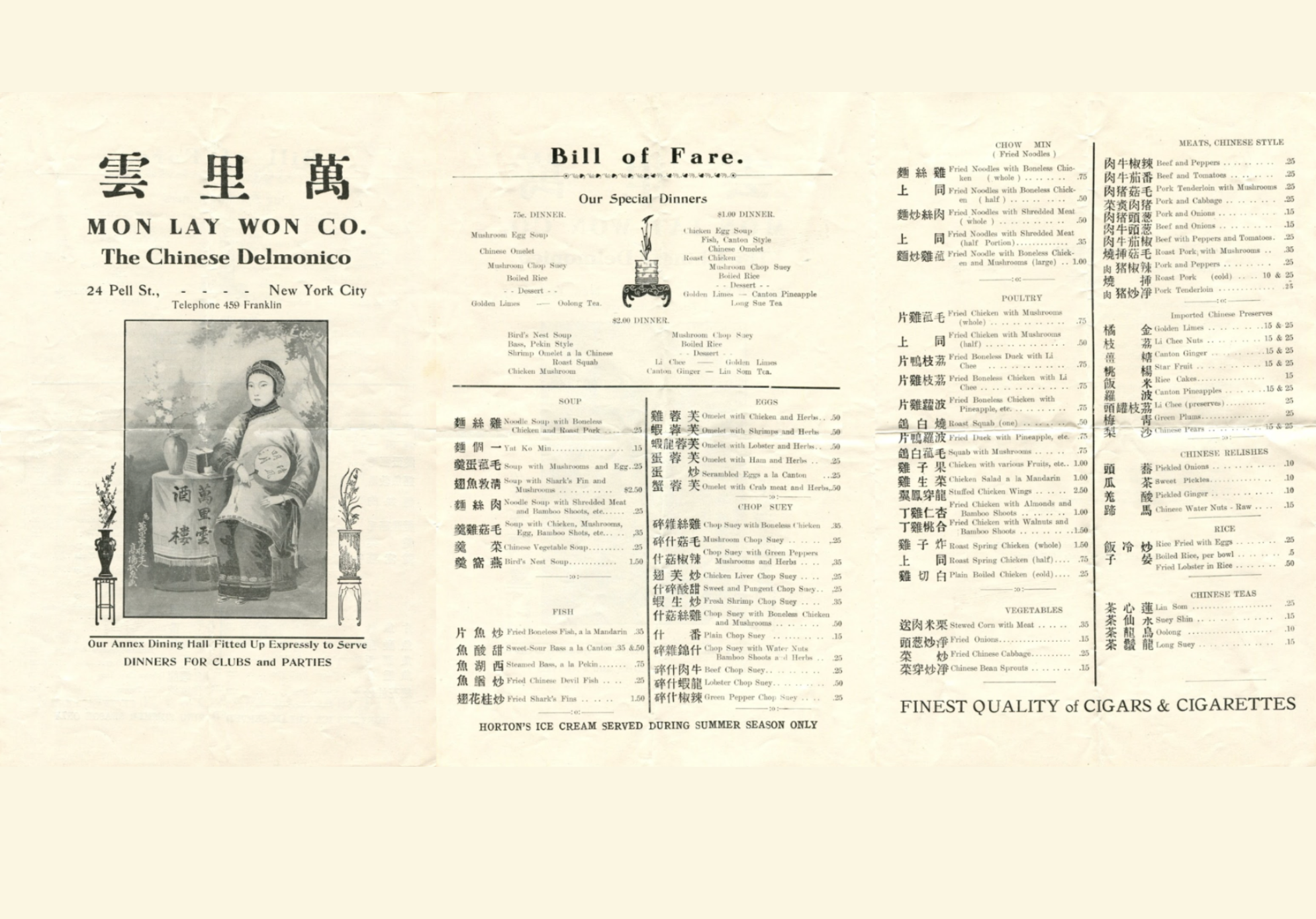

of 24 Pell Street called itself “Chinese Delmonico’s” and declared itself “The First Class Chinese Restaurant” on a menu dating circa 1890. The Mon Lay Wong menu exemplifies how Chinese Restaurants were transitioning from Chinese patrons to American diners. From the menu’s language to dish names and even entertainment offerings, Chinese restaurants rapidly adapted their ingredients and aesthetics to suit the American public.

Explore the restaurant menu below to learn more about how Mon Lay Wong contributed to Americanizing Chinese food.

Explore the Mon Lay Wong Menu

Click on an area in the image to see more information.

Chop Suey

Chop Suey gained popularity in the 1880s and 1890s as white American visitors entered Chinatown looking for a trademark “Chinese” dish. Immigrant-owned chophouses standardized mixes of vegetables and meats into “chop suey” dishes. Andrew Coe describes the first iteration of chop suey as “a stew of chicken livers and gizzards and bits of tripe, cooked with mushrooms, bamboo shoots and bean sprouts, and maybe adding celery, onions and ‘dried dragon fish.’” Chop Suey represents a critical starting point of Chinese American culinary creation. The dish combines Chinese ingredients with American tastes, transforming into a uniquely Chinese American cuisine.

The Chinese “Omelette”

Translating “蝦龍蓉芙, 蝦大蓉芙, 蛋蓉芙唐” to a series of “omelette” dishes was one way for Mon Lay Wong to appeal to upper class French dining tastes. These dishes are more similar to what modern restaurants call Egg Drop Soup or Egg Foo Young.

(Translation credit: Jiahong Chen)

The Chinese Delmonico

On the menu’s front page, the restaurant promised to offer “dinner for Clubs and Parties” and musical entertainment from the “Chinese Orchestra String Band and Songsters.” Historian Andrew Haley identified late 19th-century ethnic restaurants offering club exclusives and entertainment perks as a way to stay on top of the growing dining industry. The Chinese Delmonico could not match the original Delmonico’s prime New York location or European cuisine, the Chinese restaurant offered an exotic novelty to an adventurous middle-class diner.

20th Century Delicacies

Birds Nest Soup, made with bird saliva, and Sharks Fin Soup, made of shredded shark meat, are both luxury Chinese dishes. Though they are not often seen on American Chinese menus today, Mon Lay Wong stocked the rare-ingredient menu items to establish its image as a fine dining establishment.

The distinct selections are often highlighted when newspapers report on American’s dining in Chinatown (see New York Times’ August 15th, 1897: Prof. C.G.D. Roberts Entertained in Mott Street), or to criticize Chinese eating habits (see New York Time’s November 2nd, 1895: Bird’s Nest Soup).

Imported Preserves

Imported preserves like “Golden Limes” and “Li Chee Nuts” were popular at fine dining restaurants and for customers to buy directly from Chinese grocery stores. While restaurants capture newfound interest in Chinese culture, Chinese grocers imported preserves and other Chinese ingredients for the existing Chinese community.

Chinese grocery stores demonstrate a strong Chinese community presence. With around one-hundred thousand documented Chinese immigrants in the 1890s, only 0.02% of the United States population, grocery stores connected immigrants to food and to each other. Such is the case in advertisements like Sam Chung’s Chinese Groceries and Provisions in the Carson City (Nevada) Morning Appeal.

Specials and Menu Construction

One of the most notable features of this menu is the column format, which persists in Chinese restaurant designs through the present day. Mon Lay Wong lists their “Special Dishes” under their tea offerings, giving the same visual weight to $2.50 “Bok Nu Quai Chow” as $0.10 “Ooloong” tea. Evenly distributed columns are replaced by Western-style, fine dining menus as the decade progresses, as seen below in the 1910s menu. The columns in the 1890s menu show Mon Lay Wong in transition, still refining details like menu printing on its path to becoming an upper-class establishment.

How did this Era of Chinese Restaurants End?

During the late 1800s, as diner preferences changed, restaurants changed in response. See how an updated menu from Mon Lay Wong changed in the span of around twenty years. Changes include details like menu styling, increased Chop Suey offerings, and using a “Bill of Fare” as the title. These edits show subtle shifts towards European dining and American dining preferences, leaving behind strictly Chinese dishes and the three-column list menu format. By adapting to upper-class dining styles with the American public, Mon Lay Wong becomes a snapshot of how to be Chinese American at the turn of the 20th century. Check out historian Andrew P. Haley’s book Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920 to read more about how the middle class shaped dining culture in ethnic restaurants in the early 20th century.

Leave a Reply