Introduction to the Fairs

World’s Fairs gathered international and domestic tourists for grand displays of cultural exchange and nationalist exhibits. Among paintings, machinery, and other international wares, food became an important element to showcase national cuisine. However, the touristic nature of World’s Fairs, combined with the logistics of feeding mass crowds, made it difficult to offer traditionally prepared foods or authentic dishes.

The fairs offered tourists new entertainment opportunities, from thrill rides, art exhibits, and cultural performances, all at an international scale. The rising middle-class income allowed tourists to find leisure spending their pocket money on extravagant foods, carnival games, and global trinkets.

Organizing parties like government diplomatic offices, saw the fair as an opportunity to establish an international presence at the worldly events. Corporations and merchants saw the fairs as ways to advertise their country’s goods in order to engage in foreign commerce.

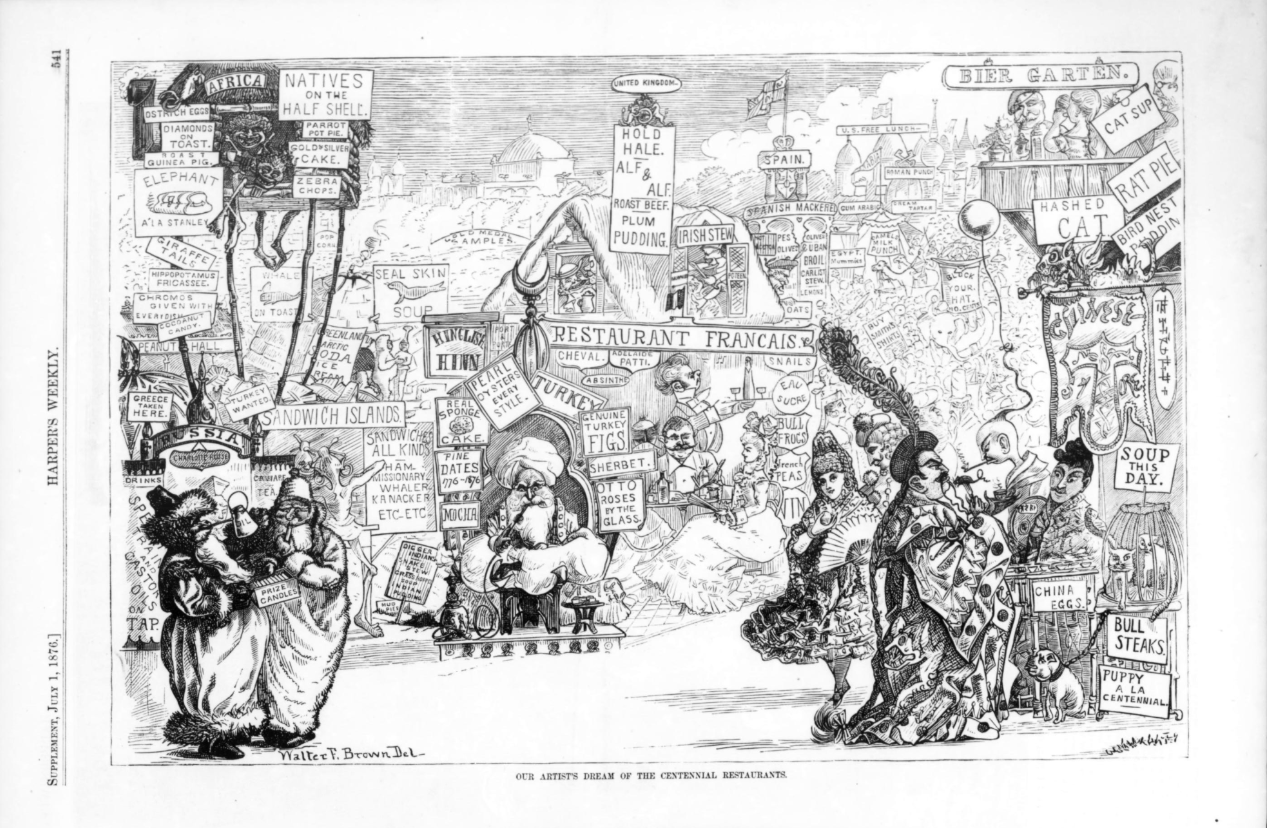

Food booths would try to match the international atmosphere at the fair, creating a distance between intentions for food to be a cultural facet and the reality of mass-produced food at the fairs. Harper’s Weekly, a popular 19th-century magazine, exaggerated international restaurants’ offerings in the political cartoon “Our Artists Dream of the Centennial Restaurants.” In the cartoon, made for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, Restaurant Francais is depicted next to a sign for African “zebra chops.” A plaque for “diamonds on toast” satirically comments on foreign imports. The rightmost side shows dishes displaying Chinese stereotypes, “Hashed Cat” and “Rat Pie.” This exaggerated look at World Fairs’ foods demonstrates how food stands could be used for national pride. Chinese food at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition and St Louis’s 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition show how Chinese American culture took shape at the hands of Fair organizers and their culinary offerings.

1893 Fair

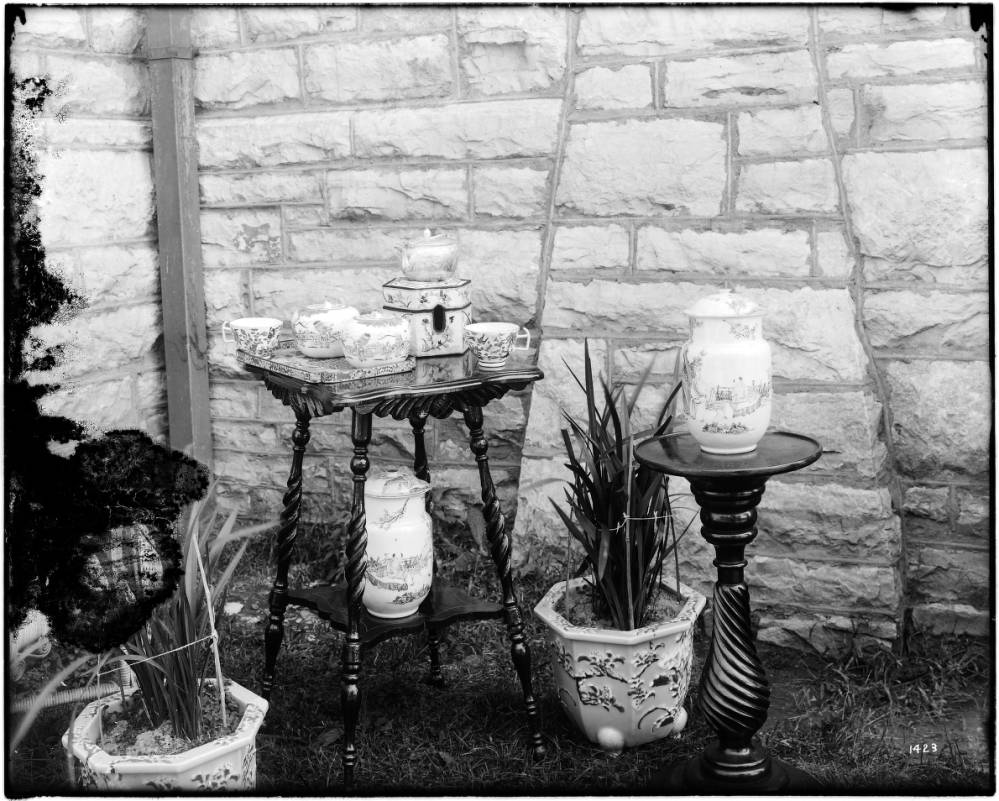

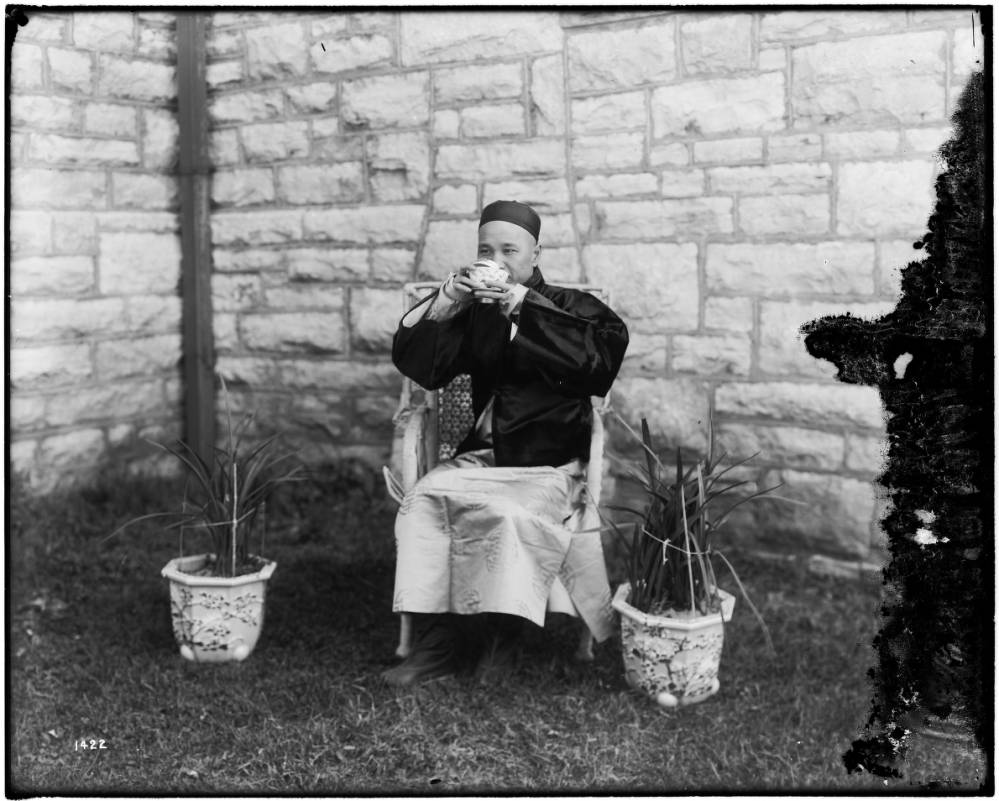

The Chinese Exhibits at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition seem extraneous to early Chinese American culture because China did not attend the event to protest the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Instead of an official Chinese government delegation, Chinese American businessmen took charge of the Chinese exhibits. Dr. Gee Woo Chan, Hong Sling, and Wong Kee came together to form the Wah Mee Exposition Company, a corporation supporting Chinese exhibits at the 1893 exposition. The Chinese American Museum of Chicago highlights many resources and item descriptions from the 1893 Exhibition in their digital collections. Additionally, Samuel C. King’s “Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933” explores the context of Chinese America during the 1893 fair even more in-depth.

Because Chinese American businessmen crafted the Chinese exhibits at the 1893 fair, displays were shaped by Chinese and American cultural backgrounds and identities. However, the fair was not a project for promoting Chinese American community. Commercializing the Chinese experience motivated the businessmen’s decision to form of the Wah Mee Exposition Company. The 1893 exhibits focus on the most marketable version of Chinese culture, but the popularity of Chinese exhibits with tourists demonstrates a contradiction between America’s cultural interest in China despite political animosity towards Chinese Americans.

When it comes to reports on the 1893 Exposition, newspapers focus on numbers and data to prove the impact of the fair. At the same time, menus continue the 1890s trend of a fusion between what was thought to be traditional authentic food (imported by recent immigrants) as well as dishes more in tune with, and thus approachable to, the standard White American middle-class diet. The 1893 planners switched between Chinese and American features wherever one culture seemed more beneficial than the other. View documents below about Chinese food at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Food at the Center of Fair Planning

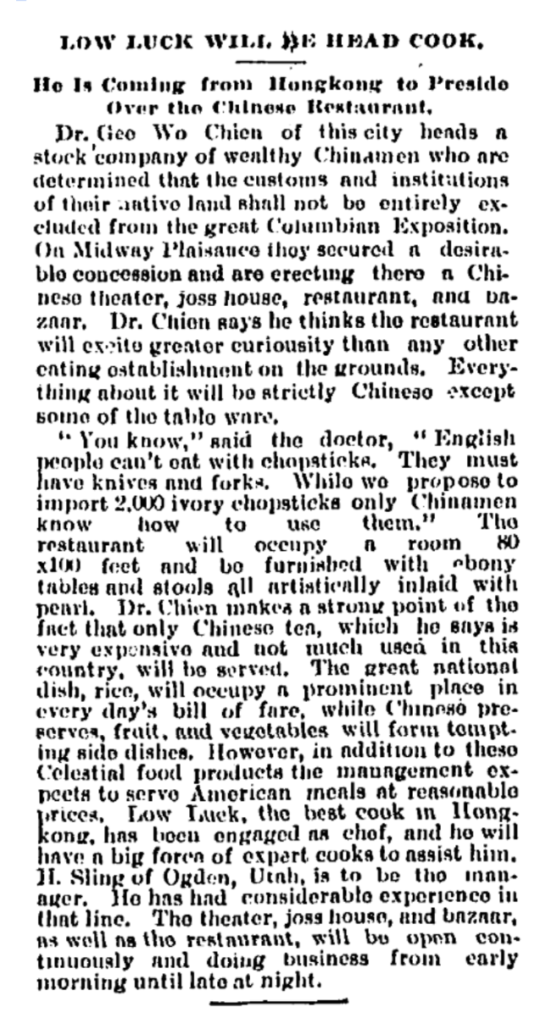

One article, “Low Luck Will Be Head Cook,” published in the Chicago Tribune on February 18, 1893, quoted Wah Mee Exposition organizers about the Chinese food:

“Everything about it will be strictly Chinese except the table ware… ‘English people can’t eat with chopsticks. They must have knives and forks. While we propose to import 2,000 ivory chopsticks only Chinamen know how to use them.’”

This quote demonstrates the planners intent to cater to Western diners. While the dishes could be cultural displays of unique ingredients, the eating method would favor the Western tradition of the fork.

Low Luck is hailed as a Hong Kong chef, which adds a geopolitical layer to how the Wah Mee Company catered to “Chinese” food. Immigrant restaurants in Chinese American enclaves tended to bring food from rural areas of China, especially from the Cantonese regions. Choosing a Hong Kong chef reflected a Westernized business selection from an area of China under Britain’s colonial influence.

See how the Tribune discussed planning for the different food areas at the Midway Plaisance.

Red sections mention food.

Orange sections mention people, including patrons and staff.

Blue sections mention building details.

Few Features Omitted

In The Great White Horse Inn – “The cooking will be strictly English, the intention being to serve the same cuts of meat, the same kinds of roast beef, the cool joints, plum pudding, imported pickles, ales, wines ,adn beers that high-living Britishers are used to having at home”

To cater to German Patrons

In the German village – “Not to be outdone by any other nation on the globe Germany will be represented on Midway Plaisance by a restaurant where visitors can secure anything their appetite crave from a pretzel and a glass of beer to a finely-prepared meal”

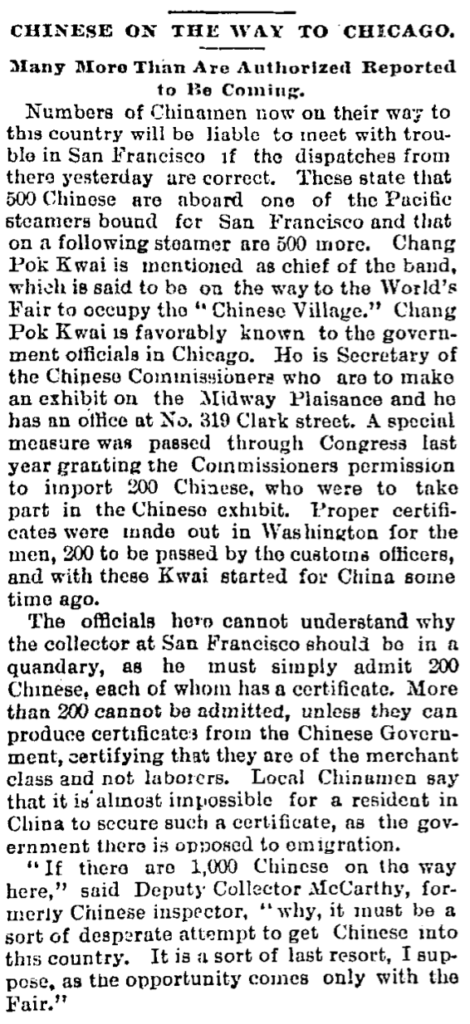

Chinese on the Way to Chicago

While the Chicago Tribune reported on how to feed hundreds of thousands of guests, Chinese workers and attendees of the Fair were under scrutiny because of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Though the Tribune estimated over 1,000 Chinese people came into the United States, only 200 were at the permission of special Congressional approval to attend the Fair. The World’s Fairs offered international entertainment and worldly cuisine, and the Columbian Exhibit portrayed Chinese culture as entertainment.

Coverage at the Fair

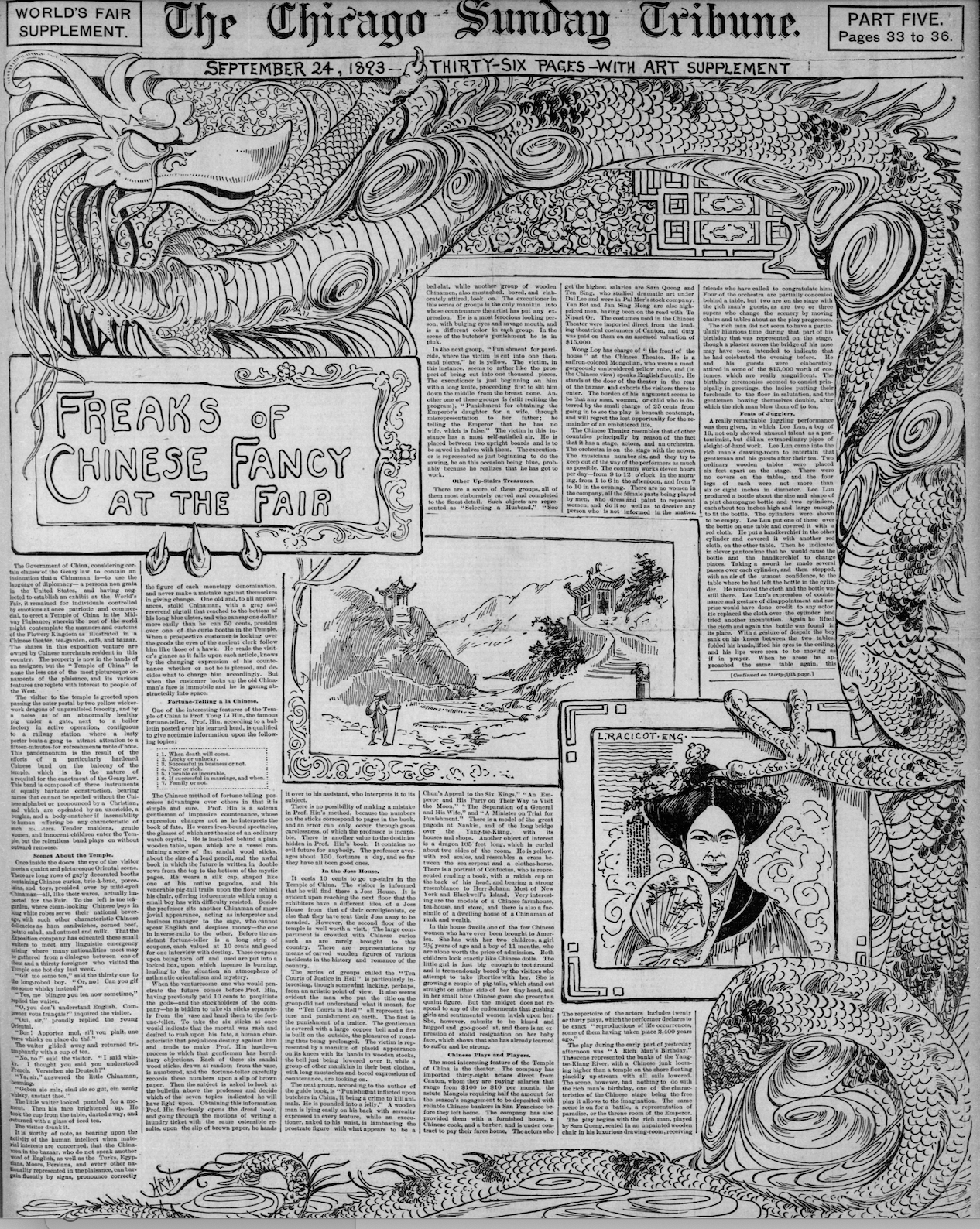

Freaks of Chinese Fancy

Despite no official delegation from China and the ongoing Chinese Exclusion Act, news spreads like “Freaks of Chinese Fancy at the Fair” showed how the American public was interested in Chinese aesthetics and culture. The article is the first page in the World’s Fair Supplement. Rich illustrations, including an ornate dragon, temple scenery, and traditional lamps, frame the special feature. The Tribune described the Chinese American organizers as “controlled by emotions at once patriotic and commercial, to erect a Temple of China.”

In the section “Scenes About the Temple,” the article sarcastically talks of “characteristic Chinese delicacies as ham sandwiches, corned beef, potato salad, and oatmeal and milk.” While entertainment such as Fortune Tellers and musical performances more easily passed as authentic Chinese culture, food had to appeal to waves of American diners while also contributing to the Chinese aesthetic, creating obvious breaks from an immersive “Chinese” experience.

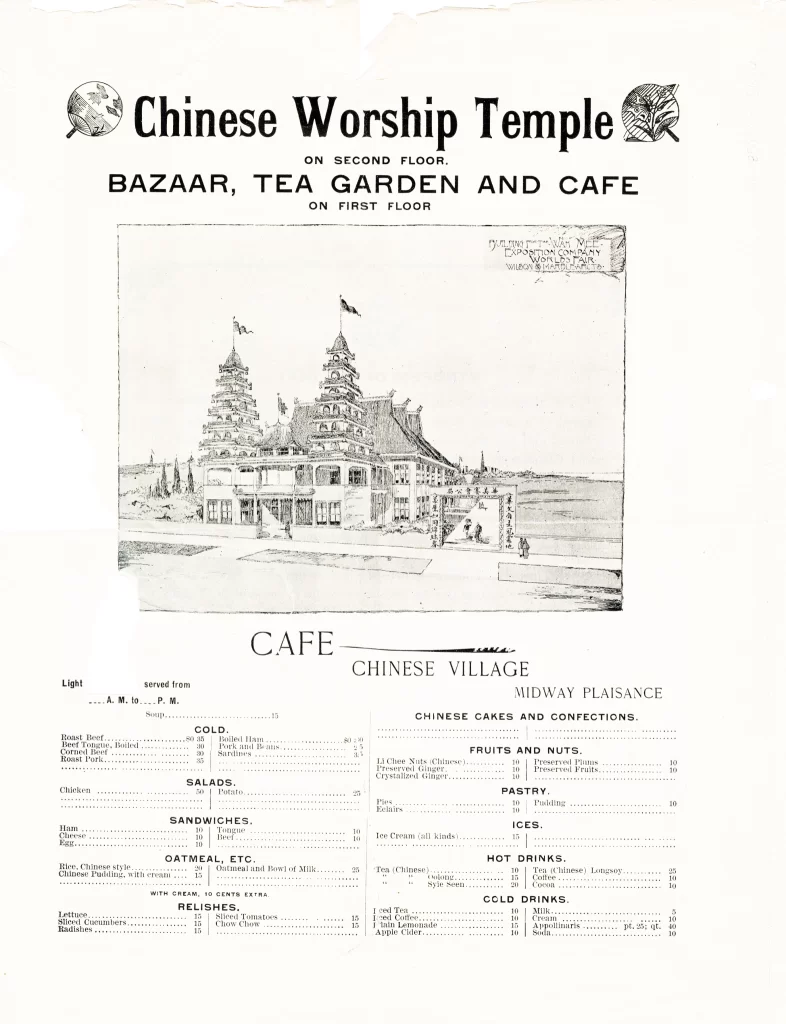

The Chinese Cafe

Despite organizers saying the Chinese Cafe would serve “everything strictly Chinese,” this menu from the Chinese Cafe shows a range of American food and Chinese food specified separately. Sections under “Cold,” “Salads,” and “Sandwiches” list standard Roast Beef, Chicken, and Ham options. “Oatmeal” brings in Chinese influence with “Rice, Chinese Style” and “Chinese Pudding.” The section “Chinese Cakes and Confections” contains “Li Chee Nuts (Chinese)” and “Tea (Chinese),” which creates a strict separation between the imported Chinese food and the presumed American food that makes up the rest of the menu.

Grace Krause further discusses this menu and more on Chinese and Chinese American authenticity in her article for the Graduate Association of Food Studies, “A Cup of Real Chinese Tea: Culinary Adventurism and the Contact Zone at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.”

One logistic reason why the Chinese Cafe’s food may have been Americanized was how the Fair was catered. In their exploration of 1893 food for their chapter “Fair-as-Foodway,” in Historical Archaeology, Rebecca Graff and Megan Edwards note the Wellington Catering Company was the only company that employed chefs and offered kitchen space for almost every restaurant at the 1893 fair. Even if Wellington staff did not have direct oversight of the cooking, “Wellington Company secured the right to require that all other companies operating restaurants at the fair buy foodstuffs through them.” In a large commercial setting like the World’s Fair, stereotypes were used by the organizers to create an experience enjoyed by all, as well as the logistics of feeding hundreds of thousands with a similar diet.

In a large commercial setting like the World’s Fair, stereotypes are created by the organizers who create an experience enjoyed by all, as well as logistics of feeding hundreds of thousands with a similar diet.

1904 – Chinese Food Exoticized among American Identity Making

The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St. Louis is known for its popularization of classic American foods, including the hamburger, the hot dog, and the ice cream cone. Food writer Robert Moss describes the 1904 fair as a critical moment for modern food to be simplified, commodified, and mass-produced. While American food was standardized, diners also looked for global flavors at the fair. Like the 1893 Columbian Exposition, there were many international food offerings at St. Louis.

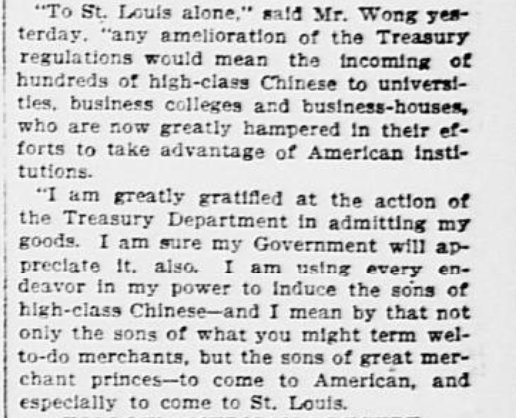

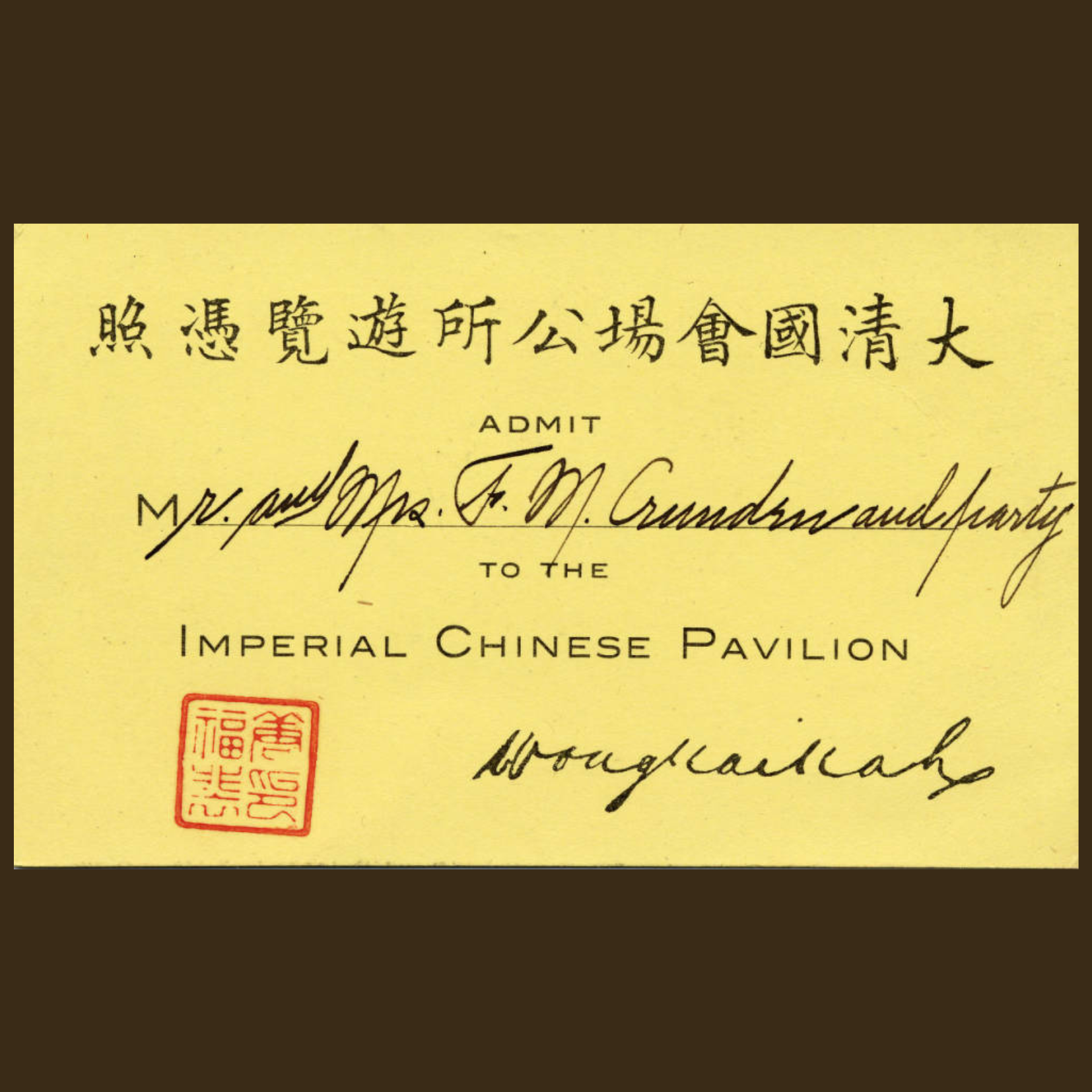

The Chinese contribution to the St. Louis fair is notably different from Chicago’s because China sent an official delegation to participate in Fair activities. In 1903, as the United States prepared for St. Louis, a piece in the San Francisco Call boldly asserted “The New China.” In this article, Wong Kai Kah, Chinese Vice Imperial Commissioner for the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, promoted potential business partnerships between the United States and China.

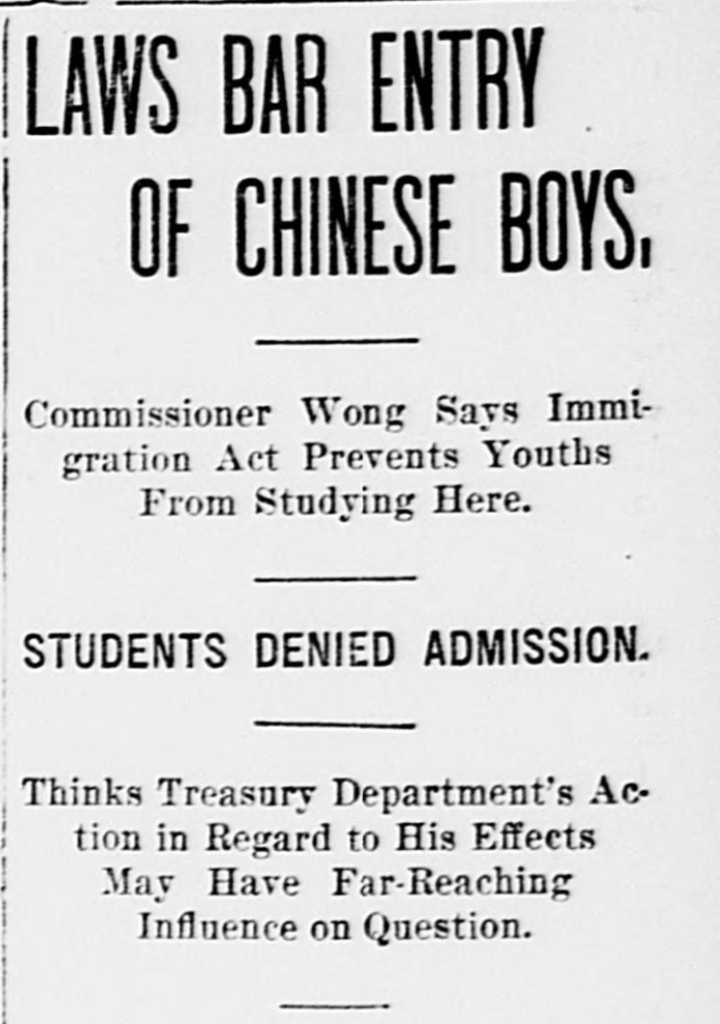

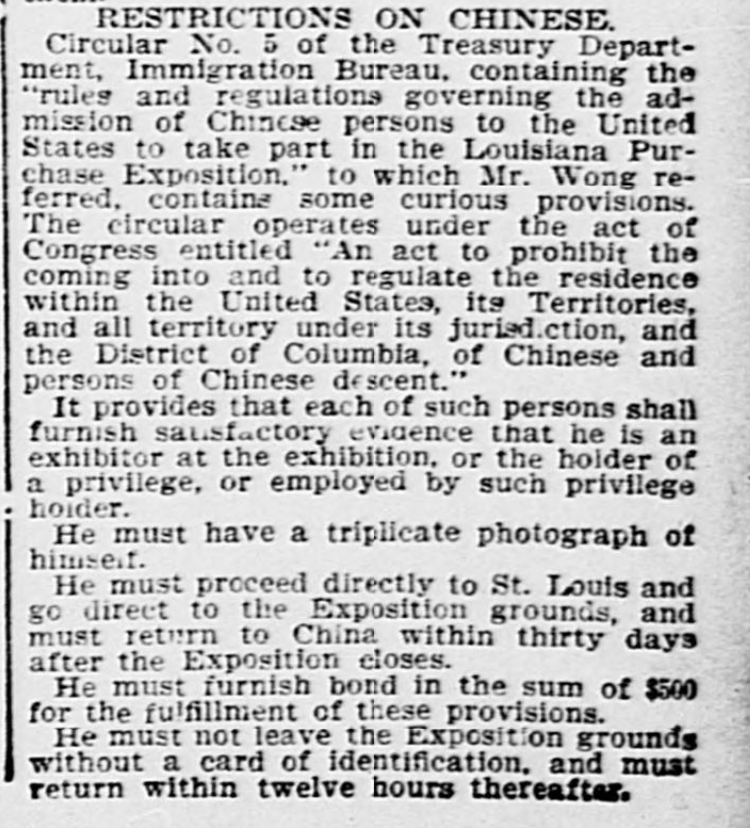

Despite China’s direct government involvement, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act still created tensions with Chinese entrants to the United States. For example, the St. Louis Republic reported on conflicts between Wong Kai Kah and American restrictions on Chinese immigration. While Kah talked of upper-class Chinese students hopefully making their way into American universities after the fair, strict regulations noted by the paper demonstrate how the United States were letting in Chinese immigrants for the St. Louis exhibition only.

At the Fair

Planning Documents

Look at the planning documents for the Chinese food exhibitions at the 1904 Fair. On the left is “Notes on China Tea,” which gives historical background on Chinese tea and describes a range of leaf origins. There is also a section on “Analysis,” where Chinese tea is compared to Indian tea chemicals. The exhibition looked into food on a cultural and scientific level, in trend with growing interest in global food and increasing scientific processes.

On the right is an inventory on Chinese “Vegetable Food Products—Agricultural Seeds.” Though many objects were brought with the intention to show off Chinese cultural goods, this section of exhibition planning documentation shows how food can also be viewed in a neutral statistical sense for scientific purposes.

After the Fairs

Records of the World’s Fairs, like the planning document above, show the extreme energy, detail, and care put into the international events. At the onset of the United States imperialist mission, China established itself as a global player, representing a refined culture, including dining. Other World’s Fairs display demeaned cultures, like the exploitative Human Zoos in St. Louis. The World’s Fairs allowed Chinese Americans and the Chinese government to shine a spotlight on their curated image of Chinese culture. However, public interest in food, arts, and architecture did not change political stances immigrant quotas or deter anti-Chinese sentiments. World’s Fairs allowed cultural posturing but took second stage to policy making.

Leave a Reply